The Culture Code

tl;dr I love this book! You should read it and then you should act as if your team being okay is the most important thing.

My new skip-level (manager’s manager) at work recently recommended The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups. I think this quote from the author’s website summarizes the book well enough, so I’ll move past that and into my thoughts.

“[Daniel Coyle] demystifies the culture-building process by identifying three key skills that generate cohesion and cooperation, and explains how diverse groups learn to function with a single mind”

I highly recommend the book if you enjoy communication books, or organizational psychology - I found it enjoyable and engaging to read, and while it reinforced some concepts I already believe, it gave me some new terminology and changed the way I think about being part of a team. That’s not to say there weren’t examples that gave me pause, and I’ll talk a little later on about the sections I disagreed with. Distilling down the ~8000 words I highlighted (8.81% of the book, thank you Kindle stats) into this post has been a great way of forcing me to reflect.

This post is structured as follows:

- My biggest priority shift after reading The Culture Code

- Existing beliefs supported by the book

- Points of contention

- My takeaway questions

- My favorite quotes

- My favorite action items

- My favorite new terminology

Let’s begin!

My biggest priority shift

My biggest mental shift after reading The Culture Code is that for me I think looking after the people around me should be my/our number #1 priority. Chapter 15 focuses on leading for proficiency, and uses Danny Meyer and his restaurants as a case study - this shift came from him and his values. It was one of my favorite/most highlighted chapters.

“I realized that how we treat each other is everything. If we do that well, everything else will fall into place.”

– Danny Meyer, quoted in chapter 15 of The Culture Code

Feeding into that shift in priorities, the first couple of chapters build a case for feeling safe as a necessary precursor to high performance. Changing how I framed interactions at work away from ‘politicking’ towards ‘defensive/lacking safety’ has helped me understand some of the dynamics better - for instance, needing to get buy-in from every party before you can start an investigation seems slow-moving and bureaucratic, but if your team has no sense of safety/trust, then hearing about a new workstream after it’s already been kicked off might make you feel out of the loop, which leads to worrying about your relevance/usefulness.

If my #1 priority is to look after my team, but I have no power to fundamentally change the structure/behaviour of my organization from the bottom, then all I can do is love/trust/respect my team as hard as I can. I can try to work on my own feelings of safety/trust to help me leave my ego behind and focus on being warm and open with my coworkers. I can act as if the actual words/decisions are less important than the process by which we get to them, and the actual people making them (because I think that they are).

Existing beliefs supported by the book

Leadership == communicating values

I already thought that one of the most important parts of leadership was crisply communicating your priorities/values to the people under you - if you’re aligned on values/priorities you can give your team autonomy and trust them to do good work, the right way. But aligning on these things is crazy hard (otherwise AI safety wouldn’t be a problem :P), so it involves a lot of nuance, repetition, and getting at things from different angles so that people can really grok what you’re saying.

The Culture Code really supports this idea. The 3rd section of the book(/the 3rd key skill) is all about Establishing Purpose, and these 2 quotes summarise leaders needing to communicate about values, and needing to communicate about them All. The. Time”.

“That’s when I knew that I had to find a way to build a language, to teach behavior. I could no longer just model the behavior and trust that people would understand and do it. I had to start naming stuff…You have priorities, whether you name them or not. If you want to grow, you’d better name them, and you’d better name the behaviors that support the priorities.”

– Danny Meyer, quoted in Chapter 15 of The Culture Code

“Be Ten Times as Clear About Your Priorities as You Think You Should Be: Inc. magazine asked executives at 600 companies to estimate the percentage of their workforce who could name the company’s top three priorities. The executives predicted that 64 percent would be able to name them. When Inc. then asked employees to name the priorities, only 2 percent could do so”

– Chapter 17 of The Culture Code

Working proximity matters

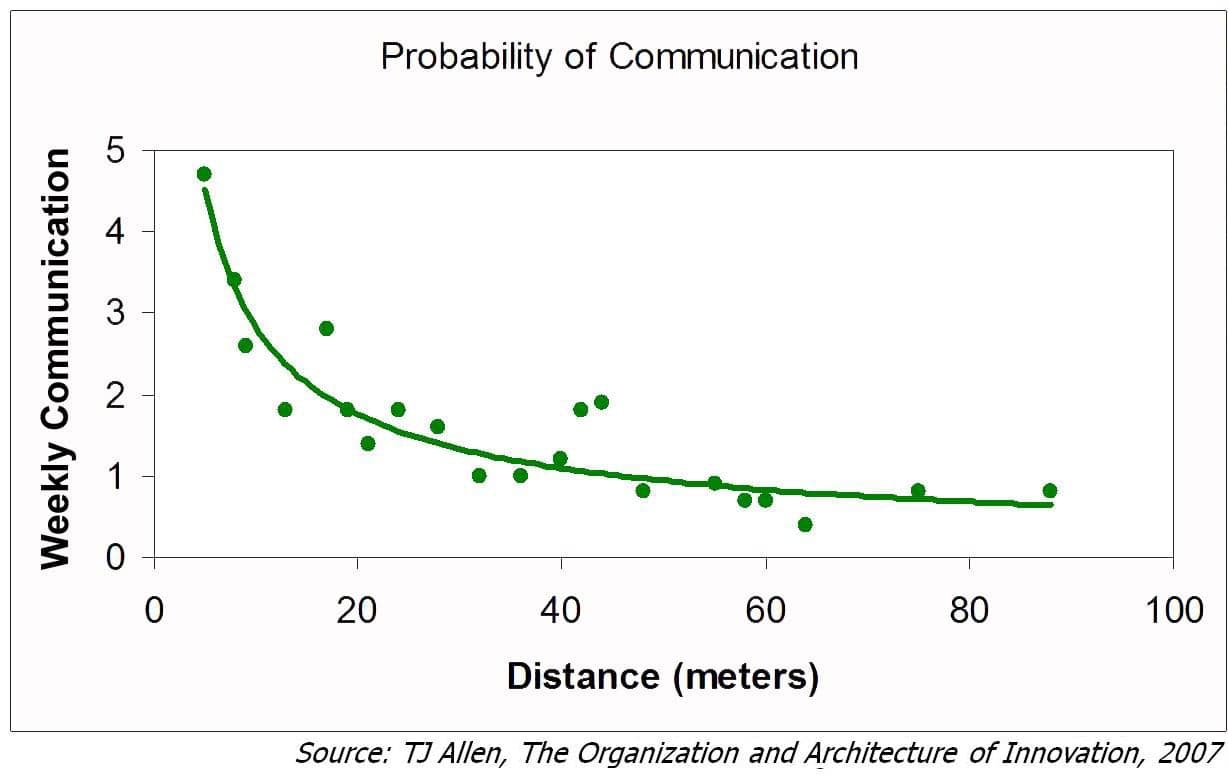

Google has a neat internal tool that shows employees how far away their desk is from any other employee they choose to query. When I interned there, I was ~8-10m away from my manager (much further than his other reports, just by my bad luck of desk placements), and it felt enormous. For the first 6 weeks I was by myself in a separate row of desks, until another intern started and was sat next to me - suddenly I had someone to talk to, to collaborate with.

This has stuck with me for years (so far, 6 of them). So reading about the Allen Curve made complete sense to me. I’ve heard people joke about how people in different buildings might as well be in different countries, but the Allen curve takes it a step further and says they don’t even have to be in different buildings, just different floors.

Points of contention

I didn’t disagree with any fundamental points, mostly just individual applications. It helped me to approach the book with a bit more skepticism than I might otherwise have done, given how strongly it supported some of my existing beliefs.

Chapter 15

The feeling radiates

Near the start of Chapter 15, our author introduces us to Danny Meyer, and describes his restaurants:

“When you walk into a Meyer restaurant, you feel that you are being cared for. This feeling radiates from the surroundings and the food but most of all from the people, who approach each interaction with familial thoughtfulness”

– Chapter 15 of The Culture Code

I haven’t been to any of the actual restaurants, but he grouped Shake Shack in with this, and the few times I’ve been to a Shake Shack I have never felt this. It weakened the whole chapter for me.

Not caring for salmon

There’s an example in Chapter 15 (about Danny Meyer’s restaurants) highlighting how his team failed to take a charitable response to a customer, and ended up charging her for a meal she “didn’t care for” but still ate half of. Meyer hears about it and immediately understands that it’s “insulting and passive-aggressive” and not the way his staff should be behaving.

It struck me because it’s not obvious to me what the correct response is, even with a maxim like “making the charitable assumption”. Perhaps the combination of that with “put us out of business with your generosity” makes it clear? I do know that tit-for-tit-for-tat (or ‘copykitten’, as Nicky Case calls it) is a better strategy than tit-for-tat (copycat/retaliatory) for building/sustaining positive relationships, and I suppose you can handle bad apples on a case-by-case basis, once it’s clear that they’re not well-intentioned, but it still caught me off-guard that this was considered such a clear example of a failure.

Leadership feedback

Laszlo Bock, former head of People Analytics at Google, recommends that leaders ask their people three questions:

- What is one thing that I currently do that you’d like me to continue to do?

- What is one thing that I don’t currently do frequently enough that you think I should do more often?

- What can I do to make you more effective?

“The key is to ask not for five or ten things but just one. That way it’s easier for people to answer. And when a leader asks for feedback in this way, it makes it safe for the people who work with them to do the same. It can get contagious.”

– Chapter 12 of The Culture Code

I think there are supposed to be 2 benefits to this - actually receiving feedback, and helping people feel as if their feedback is valuable (hence the contagious cycle - people do more of what they feel matters).

The leadership team of my current organization does this, and it feels performative/rote. It feels like something that people know they should do, but don’t fully understand why, and so don’t impart it with the sincerity required to draw out the second benefit. It feels like my feedback will become part of a statistic, not something they would want to sit down and talk with me about.

(Perhaps it is worth noting that thus far my new skip does appear to be able to do this with sincerity).

Cancelling projects

This is also why [Ed Catmull] tends to let a troubled project roll on ‘a bit too long’, as he puts it, before pulling the plug and/or restarting it with a different team. “If you do a restart before everyone is completely ready, you risk upsetting things. You have to wait until it’s clear to everyone that it needs to be restarted.”

– Chapter 16 of The Culture Code

I know that there are many things to be delicately balanced at work, but this feels more condescending to me than anything else. It feels similar to listening with an agenda - as if the leader already knows the project will need to stop, but he has to wait for his organization to catch on.

When this happens at work it hurts morale a lot. It feels like people are not being transparent with us, and creates a culture where people wait for the penny to drop.

I’m sure that both Ed Catmull and the author of The Culture Code would see it with more nuance than I felt it was presented with.

Takeaway questions

- If having trust/safety is so fundamental to an org, how do you repair one where it’s utterly broken?

- Is my org aiming to be a proficiency or a creativity org?

Favorite quotes

Safety

Given that our sense of danger is so natural and automatic, organizations have to do some pretty special things to overcome that natural trigger

– Chapter 1 of The Culture Code

Vulnerability

There’s an accelerated change to the relationship that happens when you’re able to really listen, to be incredibly present with the person. It’s like a breakthrough — “We were like this, but now we’re going to interact in a new way, and we both understand that it’s happened”

– Chapter 11 of The Culture Code

Purpose

The other feature of this list is that many of these signals could easily be viewed as obvious and redundant. For instance, do highly experienced professionals like nurses and anesthesiologists really need to be explicitly told that their role in a cardiac surgery is important? Do they really need to be informed that if they see the surgeon make a mistake, they might want to speak up? The answer, as Edmondson discovered, is a thundering yes. The value of those signals is not in their information but in the fact that they orient the team to the task and to one another. What seems like repetition is, in fact, navigation.

– Chapter 14 of The Culture Code

Structurally, there is no difference between If someone is rude, make a charitable assumption and If there’s no food, connect with one another. Both function as a conceptual beacon, creating situational awareness and providing clarity in times of potential confusion. This is why so many of Meyer’s catchphrases focus on how to respond to mistakes - simple rules can help you make complex decisions if the rules are clear enough and ingrained enough.

– Chapter 15 of The Culture Code

Favorite action items

The book has ‘Action Items’ chapters at the end of each of the 3 key skills - building on that (and drawing from the regular chapters too)these are my favorite actionable takeaways for each section.

Safety

On ego vs safety

“I used to like to try to make a lot of small clever remarks in conversation, trying to be funny, sometimes in a cutting way. Now I see how negatively those signals can impact the group. So I try to show that I’m listening. When they’re talking, I’m looking at their face, nodding, saying ‘What do you mean by that’, ‘Could you tell me more about this’, or asking their opinions about what we should do, drawing people out”

– Chapter 6 of The Culture Code

On effectively giving feedback

Researchers discovered that one particular form of feedback boosted student effort and performance so immensely that they deemed it “magical feedback. ” Students who received it chose to revise their papers far more often than students who did not, and their performance improved significantly. The feedback was not complicated. In fact, it consisted of one simple phrase. I’m giving you these comments because I have very high expectations and I know that you can reach them.

“You are part of this group. This group is special. I believe you can reach those standards.”

– Chapter 4 of The Culture Code

On effectively receiving feedback

“You know the phrase ‘Don’t shoot the messenger’?” Edmondson says. “In fact, it’s not enough to not shoot them. You have to hug the messenger and let them know how much you need that feedback. That way you can be sure that they feel safe enough to tell you the truth next time.”

– Chapter 6 of The Culture Code

Vulnerability

On listening

The most important part of creating vulnerability often resides not in what you say but in what you do not say. This means having the willpower to forgo easy opportunities to offer solutions and make suggestions. Skilled listeners do not interrupt with phrases like “Hey, here’s an idea or Let me tell you what worked for me in a similar situation because they understand that it’s not about them. They use a repertoire of gestures and phrases that keep the other person talking.

“One of the things I say most often is probably the simplest thing I say,” says Givechi. ‘Say more about that” It’s not that suggestions are off limits; rather they should be made only after you establish what Givechi calls “a scaffold of thoughtfulness”. The scaffold underlies the conversation, supporting the risks and vulnerabilities. With the scaffold, people will be supported in taking the risks that cooperation requires. Without it, the conversation collapses.

– Chapter 12 of The Culture Code

On discomfort

“Embrace the Discomfort: One of the most difficult things about creating habits of vulnerability is that it requires a group to endure two discomforts: emotional pain and a sense of inefficiency. Doing an AAR or a BrainTrust combines the repetition of digging into something that already happened ( shouldn’t we be moving forward?) with the burning awkwardness inherent in confronting unpleasant truths. But as with any workout, the key is to understand that the pain is not a problem but the path to building a stronger group.

– Chapter 12 of The Culture Code

On framing

The other thing that helps people, I think, in their move to make this part of daily life is to frame it around learning. When you talk about what you’re bad at that can either be framed as you’re pretty bad at that like that’s incompetence, or it can be learning.

I saw tons of examples of that. I saw a really vivid one at Pixar where the leader Edwin Catmull…Actually, I heard this story 10 years after it happened. That’s how resonant of a story it was. He came up to some young engineers who were working on some new way of coding, and he watched them for a while. They were kind of nervous. The boss is watching them. Then he said to them, this one sentence that they remembered 10 years later, he said, “Hey, when you guys are done, could you come up to my office and teach me how to do that?”

Super-simple, but when you frame vulnerability around learning, you create … What an incredible signal of learning and of saying, “I want to learn from you. Please learn from me.” These are simple signals, but they carry a lot of impact.”

Purpose

High-purpose environments don’t descend on groups from on high; they are dug out of the ground, over and over, as a group navigates its problems together and evolves to meet the challenges of a fast-changing world…this reflects the truth that many successful groups realize: Their greatest project is building and sustaining the group itself.

– Chapter 17 of The Culture Code

Favorite new terminology

Belonging cues

[The proto-language that humans use to form safe connection] is made up of belonging cues. Belonging cues are behaviors that create safe connection in groups. They include, among others, proximity, eye contact, energy, mimicry, turn taking, attention, body language, vocal pitch, consistency of emphasis, and whether everyone talks to everyone else in the group. Like any language, belonging cues can’t be reduced to an isolated moment but rather consist of a steady pulse of interactions within a social relationship. Their function is to answer the ancient, ever-present questions glowing in our brains: Are we safe here? What’s our future with these people? Are there dangers lurking?

Belonging cues possess three basic qualities:

- Energy: They invest in the exchange that is occurring

- Individualization: They treat the person as unique and valued

- Future orientation: They signal the relationship will continue

– Chapter 1, The Culture Code

Notifications

A notification is not an order or a command. It provides context, telling of something noticed, placing a spotlight on one discrete element of the world. Notifications are the humblest and most primitive form of communication, the equivalent of a child’s finger - point: I see this. Unlike commands, they carry unspoken questions: Do you agree? What else do you see?

This combination of notifications and open-ended questions added up to a pattern of interaction that was neither smooth nor graceful. It was clunky, unconfident, and full of repetitions. Conceptually, it resembled a person feeling his way through a dark room, sensing obstacles and navigating fitfully around them. We’re gonna have trouble stopping too…Oh yeah. We don’t have any brakes…No brakes?…Well, we have some brakes…Just mash it, mash it once.

On the face of it, these awkward moments at Pixar, the SEALs, and Gramercy Tavern don’t make sense. These groups seem to intentionally create awkward, painful interactions that look like the opposite of smooth cooperation. The fascinating thing is, however, these awkward, painful interactions generate the highly cohesive, trusting behavior necessary for smooth cooperation.

– Chapter 7, The Culture Code