How To Talk So Kids Will Listen and Listen So Kids Will Talk

We want to break the cycle of unhelpful talk that has been handed down from generation to generation, and pass on a different legacy to our children—a way of communicating that they can use for the rest of their lives, with their friends, their coworkers, their parents, their mates, and one day with children of their own.

– Adele Faber & Elaine Mazlish, How To Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk

I suspect it was Elizabeth’s post on Interpretive Labor that inspired me to add How To Talk to my To-Read list - that post gave me the language to describe a lot of things I was becoming more vividly aware of.

“No two people are alike, everyone interprets a given action a little differently. Often you need to put work in to understand what people mean. This can be literal (like straining to understand an accent), or more figurative (like remembering your chronically late friend is from a culture where punctuality is not a virtue, so it’s not a sign they don’t value you).

The work it takes to do that is interpretive labor. Interpretive labor also includes the reverse: changing what you would naturally do so that the person you are talking to will find it easier to understand.”

– Aceso Under Glass (Elizabeth’s post on Interpretive Labor)

I finally got around to reading How To Talk in August, during my recruiting trip to Sydney; spending significant amounts of time on trains and planes allowed me to get back into the habit of reading - something carpooling has led me to drift away from.

The book is focussed around kids, but I think the lessons generalize out nicely to adult interactions, and internal conversations. I thought I’d structure this post around the quotes/points I found most resonant/insightful/applicable from the book, discussing what I found in each one.

It doesn’t have to feel natural to be effective

Our mentor, Dr. Haim Ginott, came to this country from Israel as a young adult. When we first joined one of his groups, we remember complaining to him about how hard it was to change old habits: “We find ourselves starting to say something to the kids, stopping, tripping over our own tongues.”

He listened thoughtfully and then replied, “To learn a new language is not easy. For one thing, you will always speak with an accent…But for your children it will be their native tongue!”

To me, this is getting rid of the meta-negativity that comes with trying to change behavior.

Teach consequences, not punishment

We see punishment as the parent deliberately depriving a child for a set period of time or inflicting pain on him in order to teach that child a lesson. Consequences, on the other hand, come about as a natural result of the child’s behavior.

- e.g. You can’t borrow my tools anymore because you continue to leave them outside to rust

- e.g. You’ll have to do your own washing because you continue to leave things in your pockets that damage the other clothes

I like this approach a lot. Breaking out of the ‘you deserved it’ punishment mindset is incredibly hard - it’s insidious and I constantly have to battle against wanting to hurt other people for hurting me. Instead, I try to be outcome-oriented as much as possible, and engage empathy wherever I can.

We aim to say to the child “I don’t like what you did and I expect you to take care of it”. We hope that later on in life, as an adult, when he does something he regrets he’ll think to himself “what can I do to make amends - to set things right?” rather than “what I just did proves I’m an unworthy person who deserves to be punished”

They have another valuable point related to the above, that to a lot of people punishment feels like it cancels out the action - they no longer need to make amends or modify their behavior, they can simply take a punishment and move on (while feeling secretly like the hero of their story and resenting the punisher).

I guess the lesson from those two is nothing revolutionary, just good reminders that punishment is not the way to achieve my goals (with myself or other). When I notice myself being punished/feeling resentful, I try to remember that punishment doesn’t count as amends, and to let the punishment be the other person’s failure and to not let myself sink into that mode of operation - to rise above it, and try not to judge them for it.

Actions != Identity

When a child persistently behaves in any one way over a period of time, it requires great restraint on our part not to reinforce the negative behavior by shouting “there you go again!”. It takes an act of will to put aside the time to deliberately plan a campaign that will free a child from the role he’s been playing.

- e.g. a bully, lazy, bad at time management, ‘the good girl’

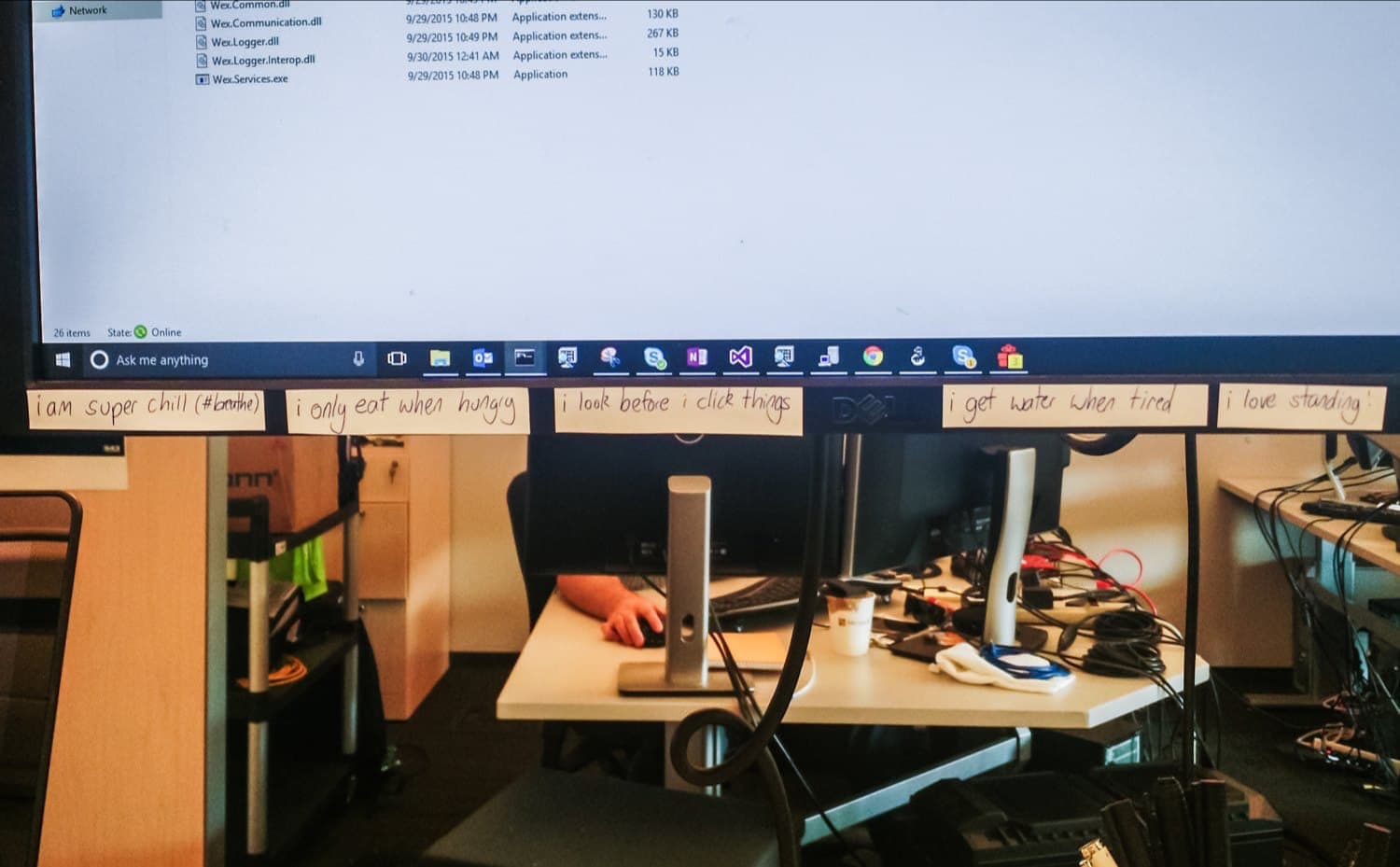

I find this important both with myself and others. I just recently put a bunch of sticky notes on my work monitor breaking some roles I’ve been settling into.

With others I try to remember that my notions of them do not (and can not) reflect some objective truth of them that I need to uncover or interact with. The goal isn’t fake interactions, but to hone in on the way that people bring out different aspects of others, and try to bring out the person they want to be.

Be Careful with Praise

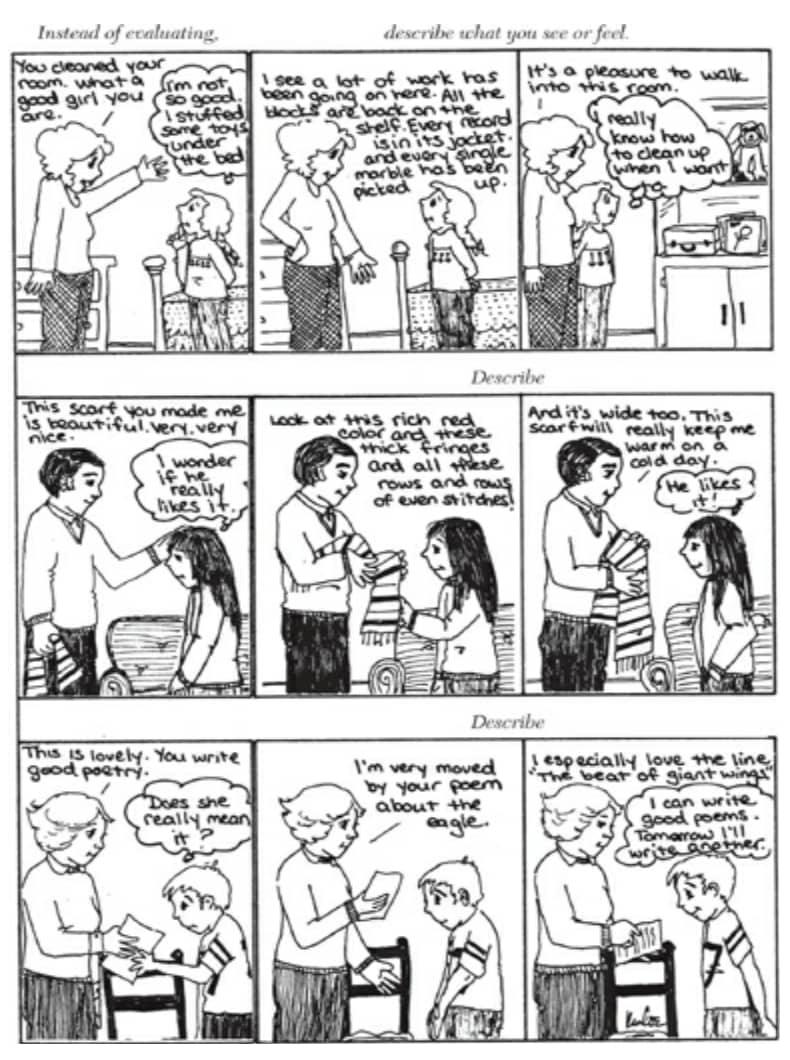

After my first few sessions with Dr. Ginott, I began to realize why my children rejected my praise as fast as I gave it. He taught me that words that evaluate—good, beautiful, fantastic—made my children as uncomfortable as you probably felt in the exercise you just did. But, most important, I learned from him that helpful praise actually comes in two parts:

- The adult describes with appreciation what he or she sees or feels

- The child, after hearing the description, is then able to praise himself

This is something that I’ve had difficult applying with my peers - I find it difficult to do without being condescending. I imagine this will improve with practice, and in the meantime it’s been interesting to observe just how often I am passing judgement. What’s trickier is that people often want that - I know I personally do. I haven’t concluded whether indulging it is necessarily problematic, but I do identify with the cartoon below, where it’s hard to trust that someone else is being authentic when all they do is say “that’s great!”.

One temptation that parents have to watch out for is the urge to praise by comparison. The danger here is that this kind of praise puts relationships on thin ice. Might the big brother feel threatened when his little brother learns to tie his shoes? Will his accomplishment be diminished? And how will big sister feel when the “baby” starts learning to read? And will the brothers be likely to work together and help each other out whith cleanups when one’s achievement depends on the other’s failure?

This rings really true for me. I find friendly competition very motivating, but as soon as I become too invested or I start to see success as necessary to my sense of self it becomes super stressful and unpleasant. It’s why I mostly don’t play non-cooperative games - I like to feel good because we achieved a goal, not because I was better than someone else.

Be on each others’ team

As adults, we realize that few solutions are permanent. What would work for the child when he was four may not work for him now that he is five; what worked in the winter may not work in the spring. Life is a continual process of adjustment and readjustment. What’s important for the child is that he continue to see himself as part of the solution rather than as part of the problem

I love this - flexibility is important. This is a good reminder to me to not resent that something’s stopped working or to feel guilty (not that guilt is ever a goal), but rather to recognize that as my situations change and I adapt, some things that worked well won’t anymore. Hopefully this is because I’m improving, but regardless, the change is simply a fact, not a judgement.

In one of my first yoga classes the instructor talked about pain, asking us to try not to categorize it as good or bad, just to make peace with its existence. This feels like a similar concept.

I find that once I can empathize and accept myself, I’m able to turn this outwards and accept that my methods of interacting with a person in order ot have optimal interactions will of course need to adapt over time as we and our relationship grow.

Engage Cooperation

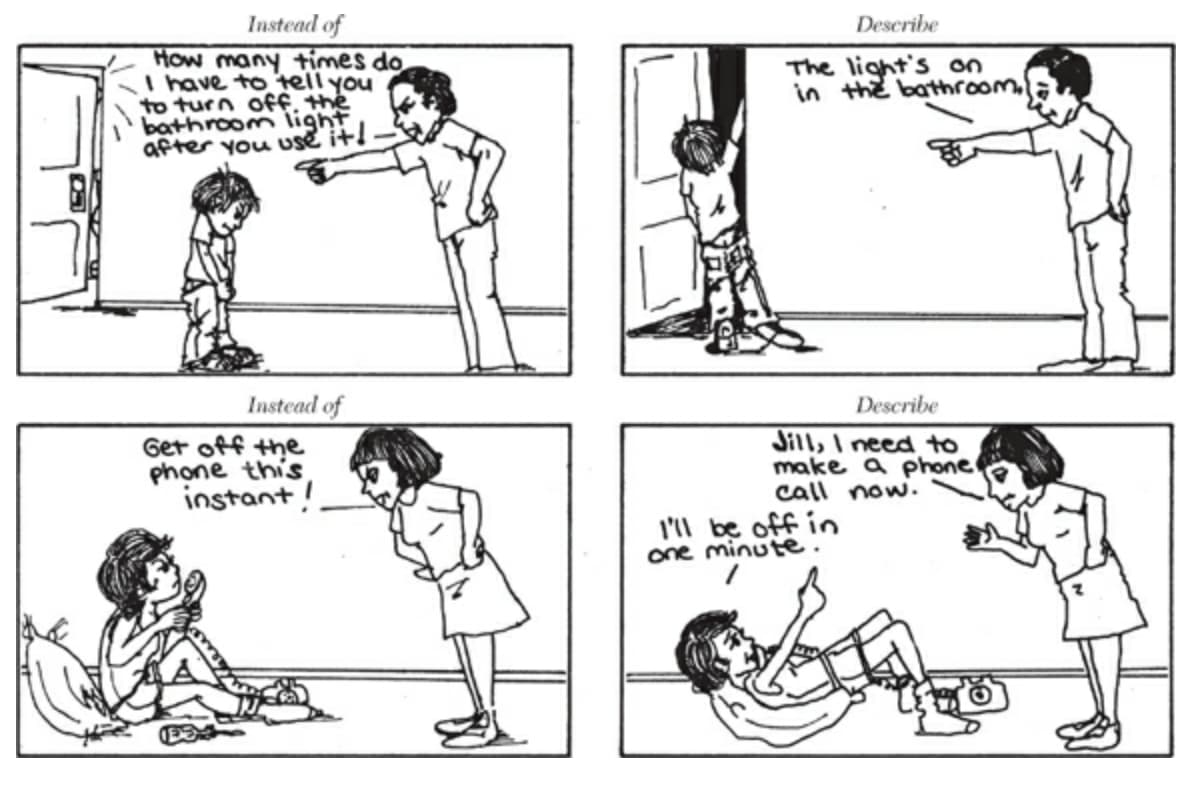

- Describe what you see or describe the problem (“The bathroom light is on”)

- Give information (“Milk spoils if left out”)

- Say it with a word (“Door!”)

- Talk about your feelings

- Write a note

I haven’t had a lot of opportunity to try this out or apply this to my life - I can easily imagine my parents trying it, getting frustrated that it doesn’t work, and stopping. I think the important lessons that I took from here are actually that

- Solutions aren’t one-size-fits-all and that’s okay.

- It can take a while to undo harm. This is okay. Keep persevering. It will necessarily take longer to solve an existing negative relationship than to start from a clean slate.

Accept feelings

I came home with a head spinning with new thoughts and a notebook full of undigested ideas:

Direct connection between how kids feel and how they behave.

When kids feel right, they’ll behave right.

How do we help them to feel right? By accepting their feelings!

Problem: Parents don’t usually accept their children’s feelings.

Steady denial of feelings can confuse and enrage kids - also teaches them not to know what their feelings are—not to trust them.

- “You don’t really feel that way.”

- “You’re just saying that because you’re tired.”

- “There’s no reason to be so upset.”

Steps to Respect Feelings

- Listen quietly and attentively

- Acknowlege their feelings with a word (“Oh . . . Mmm . . . I see . . .”)

- Give the feeling a name (“That sounds frustrating!”)

- Give the child his wish in fantasy (“I wish I could make the banana ripe for you right now!”)

Giving into wishes in fantasy is something I’ve found transferrable to giving myself permission to do things. E.g. if I’m working late I give myself permission to uber up the hill from the bus stop (not in a reluctant way, in a ‘go you if you need this then you can totally have it’ kind of way). I find more often than not I wind up walking up the hill, and feeling good about it/proud of myself for making the harder/better choice.

It doesn’t work in every scenario - it only works when there’s a time delay between the promise and choosing which action to take (the bus ride, a night’s sleep, etc), and it doesn’t work so well on things that require constant willpower. Going somewhere is 1 action, doing something for a period of time is a long series of actions. So this works much better for ‘walk up the hill’ or ‘get on the bus to work’ than it does for ‘study for 4 hours’ or ‘write 3 blog posts’. But it’s definitely useful for getting past that immediate negativity.

I can see how angry you are at your brother. Tell him what you want with words, not fists. All feelings can be accepted. Certain actions must be limited.

It can be difficult to correct without passing judgement. I know I feel the sting of criticism hard, even when it’s valid and done well. I think adding the explicit instruction of an immediate action to do instead helps remove that, because there’s no time to pause and beat yourself up. Obviously some situations are harder to provide that for, but I think that’s the most important part of constructive criticism - providing an immediate action to funnel the shame into, whether it’s applying an action or brainstorming about better alternatives.

It makes an enormous difference to a child when we accept her feelings from the get-go, without any questions. Instead of asking what’s wrong, we can simply say, “You look sad,” or “Something upset you,” or “Seems like you had a rough day.”

Statements like these help a child relax and feel free to share. She doesn’t have to defend her feelings as she would if we had said “Why do you feel sad?”. She can talk to us if she wants to, or just take comfort from our understanding.

This is something I’ve been working on applying - instead of asking people questions, using statements that open up the door to conversation if they’d like to. It’s hard to do this without making assumptions. This is similar to points they make earlier about not solving people’s problems or belittling them, just trying to empathise - “that must be rough” or rephrasing “it hurts when a friend does that”. This is tricky to do without feeling condescending! One of the exercises that I feel comes more naturally with kids, but that I think is probably still useful with peers.

Other Reading

The authors of the bestseller How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk have some great ideas that can help any parent. It’s really powerful, impressive advice. But here’s the odd thing: reading the book, I could have swore I had seen similar ideas before. And I had… When I was interviewing and researching FBI hostage negotiators.

I discovered Eric’s article 2 days after posting this, and it’s a fun comparison.